|

(from Two Wheels, June/July 1973 - courtesy of 'U.K.Vincenthusiast')

THE GENTLEMAN'S name was Cliff Horn.

That's as much as I know about him. He had scarcely won a race anywhere when he rode in the Clubman's TT on the Isle of Man in 1949. His Black Shadow Vincent recorded a fastest lap of 85.6 mph - pretty fair going considering the fastest lap in the International Service event was set at 89 mph on a. special Guzzi twin by the seasoned campaigner, Bob Foster.

Mr Horn wasn't the only rapid Vincent rider - but he was of an era of riders who understood the origins of their machines.

I often wonder if the Vincent victors of later years or the modern-day riders of carefully preserved Vincents understand exactly how difficult it was to produce an entirely new motorcycle in those hard, closing years of World War II.

The Series B Rapide was conceived when the war clouds were lifting and production of munitions lessened, the first one fired in 1946. Two years later the

Black Shadow came on the scene. It was similar but faster still.

After five years of rationing, air raids and a six-day, 60-hour regular working week, the whole nation was tired.

Machine tools were worn to shreds.

Materials, especially steel, rubber, and copper, were short, and worse still, only obtainable by officials permits, very unfairly based on pre-war consumption, and issued on the condition that 80 percent of the products would be exported.

The Vincent-HRD Company had a comparatively tiny pre-war production, and our material allocation was pitifully small, except for aluminium, which was plentiful.

All this added up a pretty grim picture, but it had to be borne in mind when deciding the main specification and detail design of our post-war machine.

Not having an extensive chain of overseas agents with specialised service equipment, the bike had to

be relatively simple to look after, but we had little hope of competing on a cost basis with the factories which had been making military motor cycles in the 500 and 350 classes.

On the other hand, the pre-war Rapide V-twin, though open to criticism in many respects, had been easily the fastest thing you could buy on two (or four) wheels, and, morever kept its tune better than high-performance singles.

THE DESIGN

The decision was almost made for us. We would capitalise on the Rapide's reputation by making an up-dated version which would be shorter in the wheelbase, lighter if possible (it wasn't), have a 50 deg V-twin 1000 cc engine built largely of aluminium, developing around 45 bhp, on 6.8:1 compression ratio to suit the poor quality petrol then available, and a clutch, primary chain and gearbox able to cope with 100 bhp for future power increases.

The frame had to have as little steel and steel tube as was possible, but in detail we wanted to incorporate any feature which would appeal to the practical rider without being merely a gimmick.

It must be mentioned that with the exception of the retired engineer who filled the post of managing director, we were all, from P. C. Vincent down, active motorcyclists, riding every day in all weathers to work, or in long distance trials, while racing men like George Brown and C. J. Williams were employed as development testers.

The front and rear duo-brakes which we had pioneered in 1934 had been so satisfactory that they could be continued unchanged, except for widening the rear hub to move the chain out far enough to clear a 4 in. tyre.

In these hubs, all four drums, the eight shoes, plus the minor bits and the taper roller bearings were identical, thus simplifying the spares situation, while the drums could be detached without disturbing the spokes; in fact, on

either wheel you could use two drums, one drum or none at all, according to requirements. The rear wheel, which was reversible, could carry a second sprocket for easy changes of ratio - very handy in long-distance trials combining miles of main road, followed by mountain sections.

With a tommy-bar pull-out axle and quickly-detachable torque arms, the wheel could be removed without using any spanners in under a minute, the operation being aided by a rear stand and a hinged section on the mudguard.

FRAME AND SUSPENSION

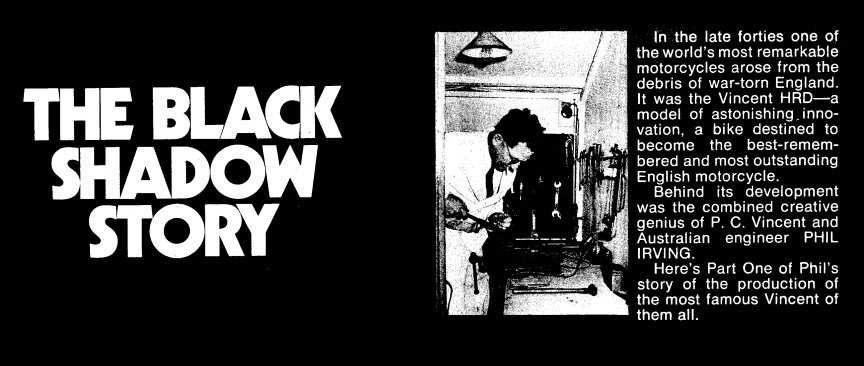

The post war machine that rebuilt a legend. This 1947 model was the original Black Shadow of that year. It's pictured here still on its assembly bench in the factory. Note the early-type Brampton forks.

Although they were a little too light for heavy sidecar work, and had no trail adjustment, the pre-war Brampton girder forks were considered to be adequate for the time being, as most of the machines would be used solo. The possibility of a change to something else was kept in mind, but had to be shelved because it was more convenient to use a design for which tools existed, and the steel required came off

Brampton's allocation, not ours.

That settled the wheels and forks, but nothing else. After much discussion it was decided to eliminate the front downtube by employing a hollow sheet-steel backbone which would also act as an oil tank, and bolt this to brackets on each cylinder head. It wasn't actually a new idea; the American Flying Merkel used it, and of course, the inclined cylinder of the P & M had acted as the front downtube for half a century. In effect, our engine would be held up by its ears and by adopting unit construction and pivoting the rear-forks directly on the gearbox tubing was done away with, yet as a frame unit the engine was far more rigid than any tubular construction could be.

With this general layout the wheelbase was reduced to 55 1/2 in. and the weight was brought well forward - the way it should be for good handling but nowadays frequently isn't. Another advantage was that it was easier to detach the whole front end and wheel it away than to juggle a bulky engine out of a loop frame.

The design allowed the rear frame pivot to be mounted very close to the final drive sprocket centre to minimise chain tension variation as the forks moved up and down (another design requirement often disregarded today) and the chain line could be widened to clear a big tyre, yet the overhang of both the final drive sprocket and the clutch from their adjacent bearings was reduced to a minimum, a factor helping to prolong chain and bearing life.

The rear forks were of P. C. Vincent's extremely rigid triangulated design which he patented

in 1928 and in 1931 the Vincent HRD was the only bike in the world produced with rear springing. This fork had never been known to break, and contrary to popular belief the unsprung weight was little, if any, greater than that of the later swinging-arm type which is often lacking in torsional strength.

In the interests of standardisation, the same taper roller bearings used in both hubs were also employed for the fork pivot, and were all mounted on hollow spindles so that the adjustment was not disturbed when the forks or wheels were detached. With this system, the entire rear end could be put together as a unit for later assembly to the powerplant, or handled separately if damaged in a crash.

ENGINE IDEAS

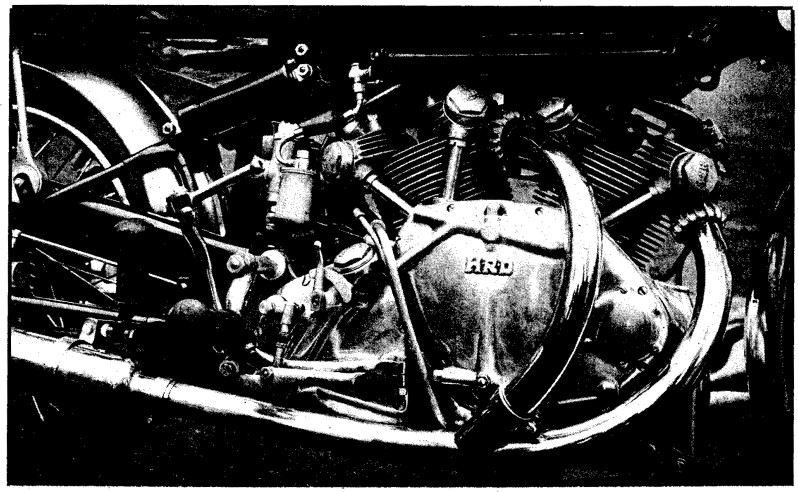

This brings us to the focal point of the design - the engine. The prewar bore of 84 mm was retained (being chosen in the first place because it was the smallest size which I could get my hand through for cleaning) and with a 90 mm stroke gave a capacity of 998 cc with the possibility of further enlargement.

The cylinder angle was settled at 50 degrees to suit available magnetoes and the rear pot was offset 1 3/4 in. to the right partly to allow identical conrods to be

mounted side by side on one crankpin, partly to provide better cooling, and partly to enable the rear exhaust pipe to clear the front inlet rocker box.

Coil valve springs were adopted in place of hair-pins because they could be more easily enclosed, but the prewar double-valve guide system with forked rockers thrusting on collars midway along the valve-stems was retained.

This system, which I cannot recall being used on any other engine, provides the equivalent of a very long guide without making the whole engine tall, while the rockers are straight and the pushrods less than 6 in. long. The entire rocker gear was enclosed, with access through four identical inspection caps per head.

Both heads were similar except that on the front one the carburettor was angled to the left to clear the rear cylinder, but at the back was over to the right to clear the generator and battery.

The heads were held down by four long bolts to the crankcase. As the bolts also carried frame stresses they were precision-made articles of high tensile steel, at one time costing nearly $4 each (extraordinarily expensive for the times), Centrifugally cast iron liners were shrunk into aluminium jackets and deeply spigotted into the crankcase, which was split vertically and also formed the gearbox shell, the rear of the chain case and the timing gear chamber.

This compartment contained the gear wheels that drove two high camshafts, a timed breather valve and the magneto through an idler gear which was originally a bronze casting. It was later changed to a forging made from the very strong aluminium alloy RR 56. This gave good service, but some local replacements apparently made from melted-down saucepans broke up very quickly, giving the light-alloy wheel an undeservedly bad reputation.

The gear-type oil pumps used in the A series engine are prone to let oil through into the sump when the bike is standing, so this type was replaced by a Pilgrim pump which has a rotating plunger that also reciprocates and acts for both pressure and scavenging.

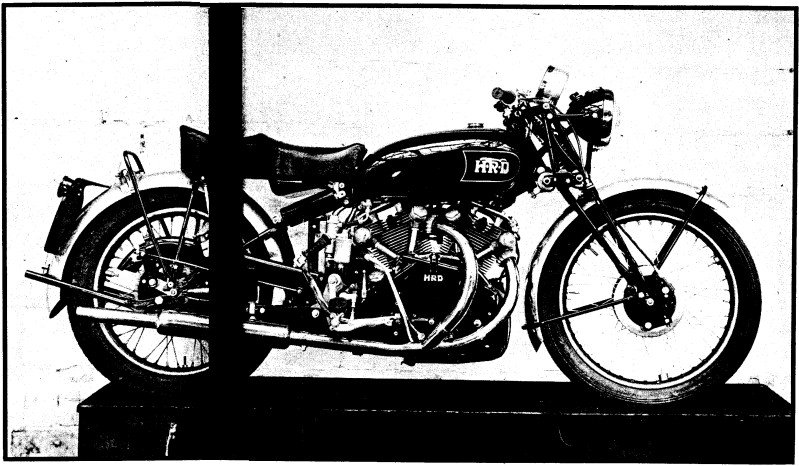

The experimental Rapide showing the brake pedal mounted on the foot-rest hanger and adjustable for height. Irving describes the gearbox filler cap/dipstick combination as "the type of sensible design appreciated by the average motorcyclist". Note the blanked-off hole for the left-hand kickstart shaft.

Pressure oil goes through one of the largest felt filters ever used in motorcycle, housed below the

front-mounted magneto (cowled for weather protection) and then through drillings in the timing cover to

the cams and cylinder bases. Scavenge oil goes back to the tank by an external pipe which passes over the

rocker boxes and supplies oil to them through jets, the idea being to use the accumulated oil in the sump to

lubricate the valve gear immediately the engine is started.

DRIVELINE DEVELOPMENT

Devising a clutch to handle

perhaps 100 bhp and yet light enough to lift with one finger wasn't easy. Several designs of servo-clutch were

built before we hit on the idea of using a drum type clutch with the shoes expanded by toggles connected to a conventional single-plate primary clutch which needed only light springs and actually could be lifted with one finger. This device later proved to be able to handle the 120 bhp obtained from supercharged engines, but was not entirely without its bad points.

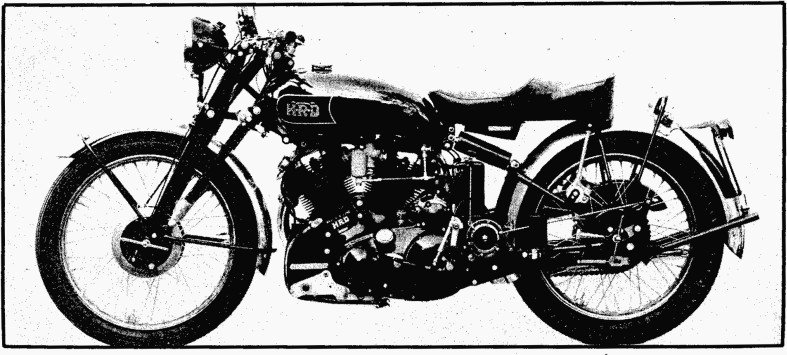

This is the later Series C Black Shadow which used the famous Girdraulic forks and an hydraulic damper at the rear. Power on this model was considerably up on the original model due to a variety of engine modifications.

It tended to be snatchy at take-off until the starting technique was acquired, and it was very sensitive to oil on the shoe linings; puzzling, because all development tests had been done on a prewar model with the entire clutch exposed to oil. No production clutch would grip under these circumstances, so the layout on the new power unit had to be redesigned to isolate the clutch from oil, unavoidably increasing the width by half an inch to 22 in.

The spinning weight was also rather too great, making the gear change a rather leisurely process, but this clutch stood up well to violent abuse, even on speedway outfits and hillclimb cars without much trouble.

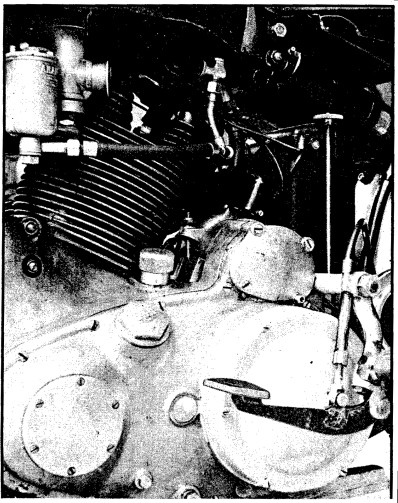

This is the Series B Rapide, with the small external indicator lever which could also be used for gear selection. Note that the lefthand propstand is down and the righthand side up. This model also has the dual seat with toolbox beneath.

The fourspeed box had three close ratios of 1, 1.19, and 1.6 with a lowish bottom of 2.6 to 1. This gave overall ratios of 3.5, 4.2, 5.5 and 9.1, so that the engine speed was only 4600 at 100 mph, and 3700 when cruising at 80, yet by running up to 5800, 80 mph was possible in second.

The change was effected by a camplate with two snakey grooves, bevel driven from the positive-stop

ratchet operated by the foot-lever. The ratchet mechanism had adjustments which had to be made in the correct sequence to get a precise change, but many riders failed to grasp this and then blamed the box for bad changing.

The change pedal was originally pivotted on the footrest hanger, but this was not always satisfactory so eventually the pedal was moved back to the box.

Finding neutral with a foot change is always a bit of a nuisance, so a small external lever was provided to indicate what gear you were in. This could also be used to change gear manually,

For the convenience of Continental chair-men or someone with a gammy leg, the kickstarter shaft was positioned so that it could extend right through the box to take a special left-hand pedal, and although this provision complicated the design somewhat, it was often greatly appreciated. So was the ability to check and top up the gearbox with a dip stick underneath a knurled filler cap.

Aluminium was used extensively for mudguards, engine plates and so forth, and stainless steel was preferred instead of chrome-plated mild steel for brake rods, banjo bolts, tommy-bar axles and similar parts, which still polish up well after 25 years' exposure. A dual seat with tool tray beneath it was specially moulded by Ferdax, this being probably the first production dual seat, although the idea was originated by Velocette for racing many years before.

ALTOGETHER THE FASTEST!

The result of all this work and thought was a machine scaling 453 lb with full equipment, tools and oil, but no fuel. This weight was disappointingly a little more than was expected, but was still 100 lb or so less than contemporary big machines.

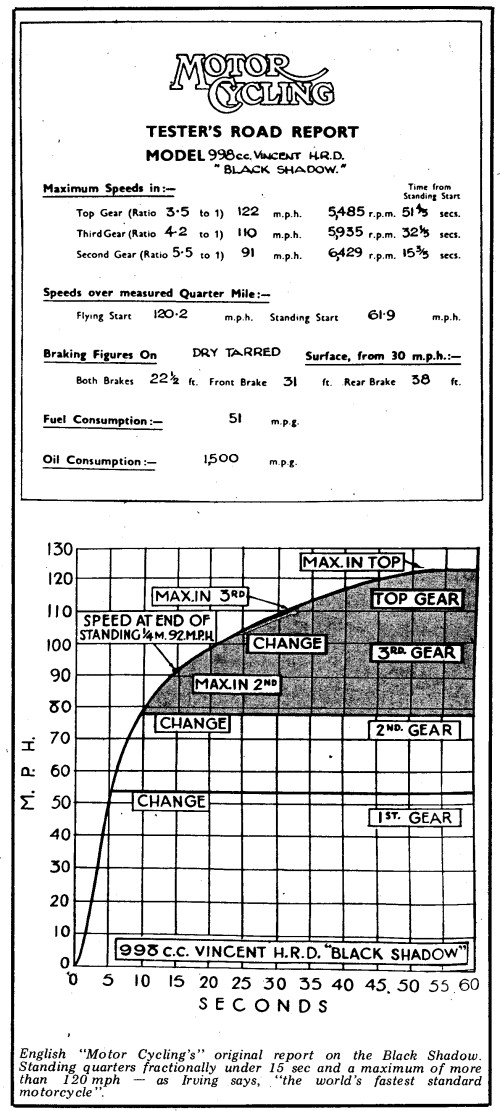

With small carburettors, 6.8:1 compression ratio, and mild cams providing 45 bhp at 5600 rpm the prototype attained 80, 104 and 112 mph in the three upper ratios, and subsequent production bikes equalled these figures in road tests by the motorcycling Press.

We didn't boast about it though - just adopted the slogan "The world's fastest standard motor-cycle!"

|